Sorting colors is a canonical example of something easy to formulate, however, unsolvable in the sense we expect. Is not that is computationally difficult. Is literally unsolvable due to the nature of what we mean when we say sorting. So lets start with a quick definition of sorting. Sorting is a procedure that imposes some kind of ordering based on a metric. There are ordable objects, as well as un-ordable object. The difference between these two types might be as simple to explain as saying to someone to order movies. They might come with a solution by ordering them by their IMDB ratting, but this is not what we asked. There is no inherit “scale” of a movie, neither of a fruit. On the contrary, Ordable objects exist in a metric space, which is a whole can of worms on its own to understand, but a simple explanation is that to exist in a metric space, you need a notion of distance.

Distance

Distance is a difficult topic to explain without diving into hard mafs. A simple explanation is that there needs to exist a distance metric that satisfies these qualities:

- triangle inequality

- symmetry

- definition of a zero distance

The numbers we are used to work in our everyday life have this notion of distance defined in several ways, and some of them are: manhattan (l1) distance, euclidian distance, etc.

But colors have a defined metric space, they are fundamentally numbers…

Yes! Very true that we can express colors in a number system, as RGB, or HSV, or LAB, etc. This definition of colors has its benefits, like in LAB space, we can even have distance between two colors. Not perfect always, but it exists and it is good enough. It satisfies the distance metric qualities, but still. Distance between two points is not how we sort. Fundamentally, is because we have RGB, or better 3 dimensions. Sorting is only defined in a single dimension. Easy, we can sort in each dimension separately. Not so fast, that creates issue with how we perceive color. Where does pink fit in this method?

But wait, there is more…

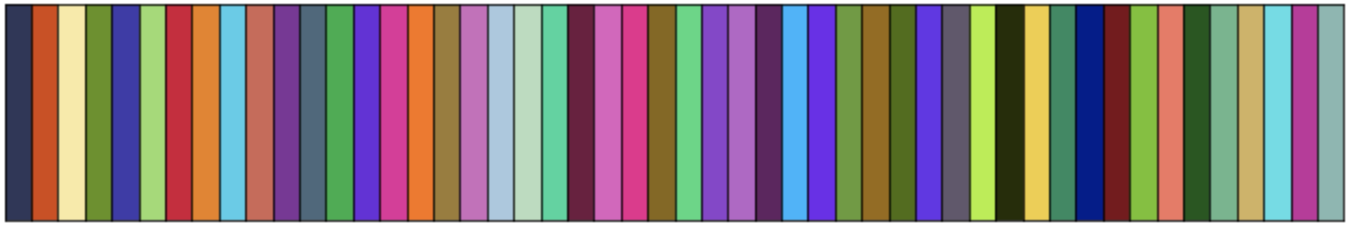

Let’s start with an example. We generate some random colors in RGB space.

Not all hope is lost, we still can sort colors, as long as we associate a number with a RGB value. And these special numbers should relatively be expressive of the distance in the higher dimensions. Meaning, our blue and dark blue “numbers” should be the same distance as blue and dark blue in RGB. Wait we already have a way to accomplish that, dimensionality reduction. Throw PCA to this problem and be done with it.

Well that was anti-climactic. PCA did nothing basically! That is because PCA was not developed for this task, and it was created in the 40s, where it was used on much interesting useful problems, rather than on color sorting. Intuitively PCA reduces dimensions by linearly combining the input dimensions (3 in our case), and only keeps the one with the most variation (expressiveness). However, RGB or any other color representation, is already reduced to the maximum, there is no redundant information. Each dimension matters.

However, there are other methods that are more recent, and perform better. Let’s explore!

Newer, better…not always

t-SNE is a method developed in 2008 and in principle, it uses some sampling tricks to push-and-pull the high dimensional objects proportionally to their high dimension distance. This sounds like a solution to our problem.

This is worse than PCA. How come? Because, the devil lies in the details of my explanation. The push-and-pull method and sampling do not guarantee that the distance will be kept. This method works well with various datasets, but does not have much mathematical theory behind it on why it works. So no guarantee, and apparently does not work for colors.

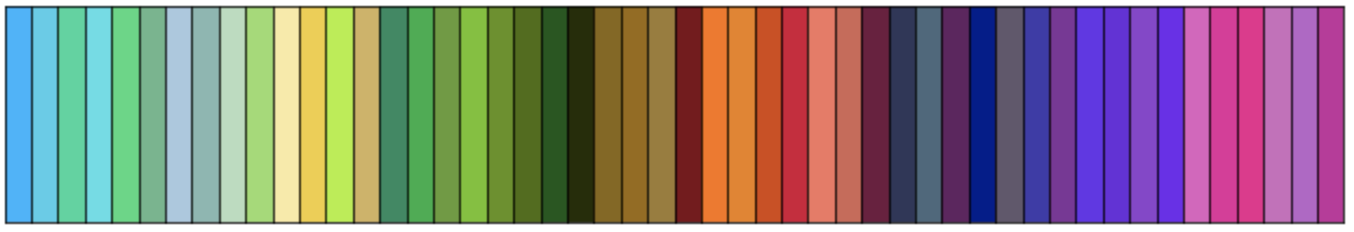

However, the secret here that t-SNE method is not all bad news. It gave mathematicians a goal, conceptually. They got to work and made a new method with harder guarantees and sound theoretical background. The method is called UMAP (read more, or watch here) and its a topological manifold method that projects dimensions into lower dimensions. The theory behind it is hard, however, we don’t need the theory to apply it. We only need a library implemented by someone smarter than us. And the results:

And tada, there we have it. A very good “natural” sorting of colors.